Teaching Qualifications

2018 Senior Fellow, Higher Education Academy (SFHEA) No: PR141532

2007 Certificate IV, Training and Assessment

Teaching Related Publications

Sigrid Zahner & Andy Buchanan. (2021). Brick Meets Pixel. 2021 Alliance for the Arts in Research Universities National Conference: The Case for Art.

Buchanan, A. (2020). A problem with questions: Improvisation and unforeseen epistemology in animation practice. Animation Practice, Process & Production, 9(1), 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1386/ap3_000014_1

2012 Australian Teachers of Media (ATOM) Award

Winner, Best Education Resource for ‘Tagged’ learning package (role: Instructional Designer)

Philosophy of Teaching and Learning

Summary of Teaching and Learning Experience

I believe that alongside discipline-specific knowledge, effective teaching is a skill that requires continual improvement. I have developed my pedagogical skills over 15 years of teaching, achieving excellent results, growth and professional development across cultures, programs, and student levels – from diploma level to Ph.D. I have experience leading multiple degree programs (BA Animation Design, BSc Multimedia), and based on this leadership experience, was appointed as a Senior Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (UK). I am an award-winning instructional designer (ATOM Awards Australia, Best Educational Design), and have served as an education consultant to the Australian government (ACMA, Cyber-Safety Division). I have developed new animation degree programs, managed programs undergoing accreditation review, and managed major plan of study revisions at, as well as developing many new courses (a link to list of all courses is available below). I have worked across the breadth of creative arts education and beyond; for example, I worked with master storytellers and communication experts to design and deliver an innovative science communication program, subsequently funded by the National Science Foundation (USA). I have received funding for the development and integration of intercultural pedagogies, and for excellence in new course development (Purdue University, USA). I have been both a willing mentee and peer mentor, with numerous items in my list of publications demonstrating collaborations with peers, junior faculty and with graduate students.

Please also see: Statement of Diversity and Inclusivity

Intellectual (and Creative) Emancipation

My teaching philosophy is grounded in the principle of intellectual emancipation, which posits a collaborative and transformative learning process built on mutual respect and shared exploration between students and instructors. This principle, articulated by Jacques Rancière in The Ignorant Schoolmaster, (1981) diverges from the conventional belief that education involves the mere transfer of knowledge from an instructor to a passive recipient. Instead, it positions the learning process as a collaborative endeavor based on the presumption of intellectual equality and respect for individual differences.

This approach rejects the notion that educational achievement occurs when some objective knowledge commodity is transferred from teacher to student. Instead, I see the education process as one that is collaborative and transformative, rather than transactional. This process is political, and emancipatory, and I think this is what makes education so rewarding as a profession. This approach is particularly relevant to education in the creative arts, as it sees education itself as a creative, rather than transmissive process, a view that aligns well with contemporary models of experiential education and other constructivist principles.

The creative process of any expressive art form including animation is often very personal. The stories and content we choose to share in these forms can be sensitive, as our ideas can be difficult to explain or express in intermediary formats. And yet, we must, if we are to collaborate towards affective impact on our audiences. I believe it is crucial that students feel empowered to direct their own expression, rather than feeling they must conform to rigid faculty expectations, or to prove they have memorized the ‘right version’ of the relevant knowledge.

Experimentation and Experimentalism

I believe that innovation is crucial for success in the creative arts – we must progress, not simply attain skills. This is especially true in animation, where technological innovations move so quickly. Creative innovation requires risk. Genuine risk requires occasional failure, and students must be supported in their risk-taking endeavors. This requires a delicate balance between excellence (maintaining high standards of practice) and the proper management of genuine risk through rigorous experimentation.

I believe student assessment must be structured such that risk and experimentation is encouraged, including assessment of process and outcome that genuinely supports improvement and innovation, rather than ‘playing it safe’. I believe this to be essential for fostering creativity, problem-solving skills, and deep understanding, which are highly valued in the creative arts and technology fields, and my qualifications in educational design have provided skills to manage this effectively. Challenges include the need for clear ongoing communication, availability and approachability, and dedication from faculty.

I believe that fostering an experimentalist attitude towards practice in the creative arts creates unique achievers with deep knowledge, and is an excellent general teaching principle. Of course, the relevance of this approach will vary in different stages and different courses within a degree program.

Customised Pedagogies for Creative Education

With the above in mind, throughout the stages of an academic career, students may require different challenges and influences from faculty.

During the foundations period, where visual, technical, and conceptual skills are first developing and revealing themselves to students, the principles of constructivism and participation from faculty through close guidance and ‘scaffolding’ may be most appropriate. By offering open ended questions and challenges in problem based, or project based learning scenarios, students can efficiently add skills to their personal constellation of knowledge. Competency based approaches can be used for basic software instruction (though I do not believe software instruction should play a major role in higher education programs, in general).

I believe senior undergraduate students in animation and related arts benefit from a studio production model where students can specialize in different aspects of animation production, and collaborate between specializations, with deliberate experience sharing opportunities. Student work should be seen and reviewed frequently both within the group and more widely (echoing the idea of sharing ‘dailies’ or ‘rushes’ in animation production). I believe strongly in the value of ongoing and open critique of work in progress. In this stage, I believe it is important that student work should reach a public audience, so that the reality of affective audience responses becomes a genuine factor in the development of practice and the fulfillment that it brings. This creates intrinsic, rather than extrinsic motivation for excellence, and builds skills in teamwork, communication and cognitive empathy with audiences.

Finally, graduate students that are working on post-capstone creative practice as well as those engaging in research benefit from the principles of practice-based research and the idea of the ‘reflective practitioner’ (after Donald Schön). Based on the ‘action research cycle’, practice-based research methodologies can formalise the integration of theory and practice. For example, the model of the Iterative Cyclic Web (Smith and Dean, 2009) formally integrates research and creative practice into ‘research led practice’. I believe it is particularly useful for practice-based research students to be supported in achieving epistemological clarity in the formal aspects of their research and creative work. This pedagogical stage is often customised at the level of the project and the individual researcher. Student (researcher) driven pedagogies are appropriate at this level, due to the inherently interdisciplinary nature of animation studies.

Courses Delivered

ANIMATION, 3D, MULTIMEDIA AND GAME DESIGN

- Animation Foundations

- Introduction to Animation (3D)

- Drawing Acting and Scripts for Animation

- Drawing 1

- Drawing 2

- 3D Modeling

- Animation 1 (studio)

- Animation 2 (studio)

- Animation 3 (studio)

- Animation 4 (studio)

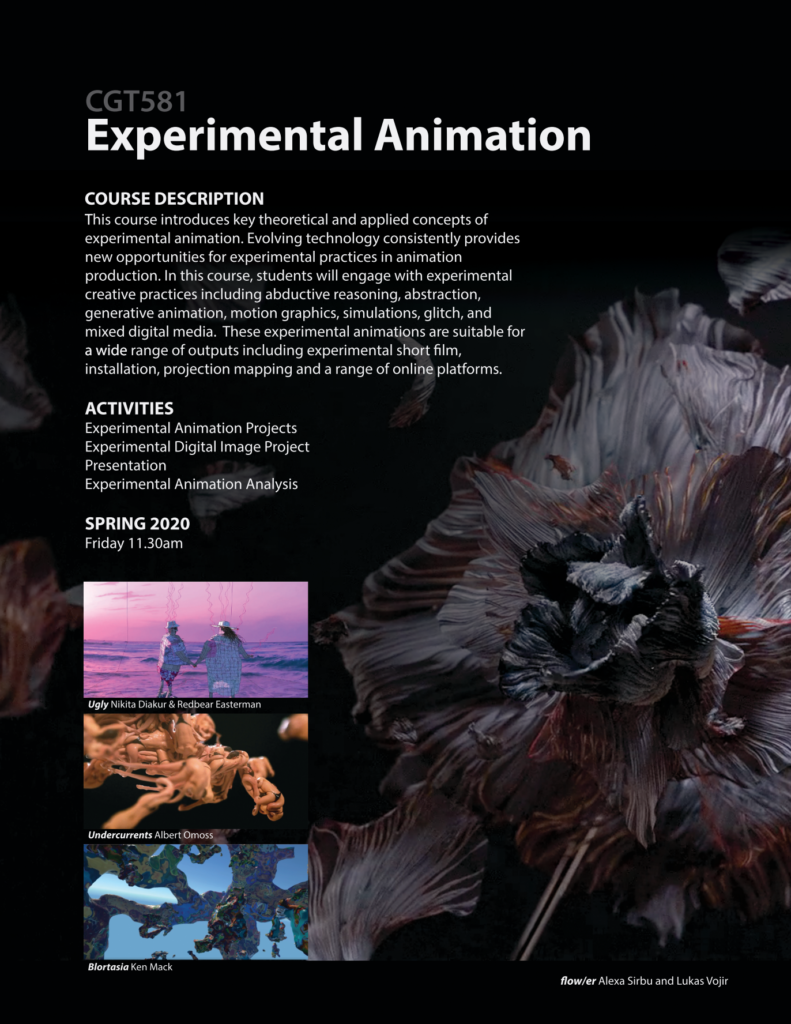

- Experimental Animation

- Animation History, Technology and Technique

- Brick Meets Pixel (experimental stop-motion and material expression)

- Introduction to Game Design

- Game Design Psychology

- Multimedia Product Authoring

- Multimedia Project Management

- Introduction to Compositing and Visual Effects

- Digital Video and Audio

- Senior/Capstone Project (Animation, Computer Graphics)

GRAPHIC DESIGN

- Basic Design (digital design foundations)

- Graphic Design 2

- Photography 1

- Digital Design 1

- Digital Design 3

- Senior/Capstone Project (Graphic Design)

GRADUATE RESEARCH

- Master’s research supervision – Animation, Computer Graphics and Creative Media

- Masters project supervision – Animation and Interactive Media

- PhD research supervision – Computer Graphics Technology

Sample Course Syllabus

CGT123 – Animation Foundations (Freshman Undergraduate)

CGT591 – Experimental Animation (Graduate)